The Rio Grande Valley's historical heritage reaches far into the past as early indigenous Indian nomadic tribes inhabited the area as much as 11,000 years ago.

Settlement and development of the RGV began in the 1700s when Spanish

explorers traveled north from Mexico in search of treasures; gold,

silver and salt.

The Spanish established missions throughout Southern and Eastern Texas

but they were met with failure due to harsh conditions and unfriendly

natives.

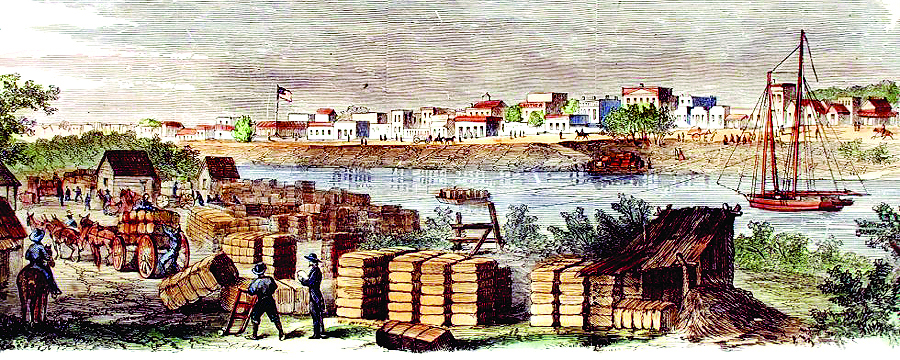

The Valley did not see much development until the United States Civil

War during which time the Port of Matamoros became an important supply

depot for the Confederacy. At one time early on, the Anglo population of

Matamoros exceeded the Hispanic population by such a large margin that

there was an English language newspaper published there.

After the Civil War and the Mexican American War land speculators, such

as Richard King, John H. Shary and Lloyd M. Bentsen to name just a few,

brought irrigation to the Valley taking advantage of the tropical

climate and turning it into a "Magic Valley" where crops could be grown

all year 'round. In the early 1900s they promoted this concept heavily

in the Midwestern United States and even arranged for private trains to

bring prospective land buyers to the region. Once here they were given

the royal treatment, wined, dined and taken on tours of the areas citrus

groves and truck farms which had by this time become successful on a

large scale.

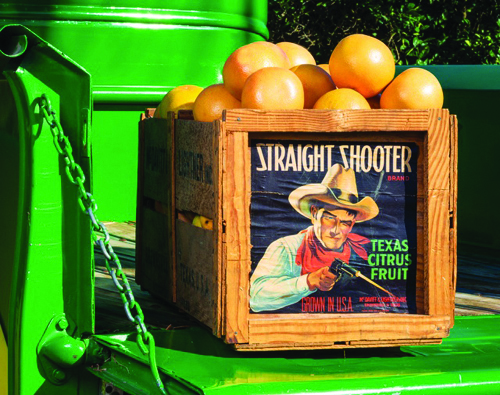

Texas has become the third largest citrus producer in the US with the

majority being grown here in the Rio Grande Valley. In addition to

citrus fruits, the Valley produces a wide variety of vegetables as well

as cotton and sugarcane.

In the 1960s the Valley saw the introduction of

maquiladoras.

A maquiladora (makilaˈdoɾa) is a manufacturing operation in a free

trade zone (FTZ), where factories import material and equipment on a

duty-free and tariff-free basis for assembly, processing, or

manufacturing and then export the assembled, processed and/or

manufactured products, sometimes back to the raw materials' country of

origin. The maquiladoras became attractive to the US firms due to

availability of cheap labor, devaluations of peso and favorable changes

in the US customs laws. In 1985, maquiladoras overtook tourism in Mexico

as the largest source of foreign exchange, and since 1996 they have

been the second largest industry in Mexico behind the petroleum

industry.

The 1960s also brought another "cash crop" to the Rio Grande Valley.

Because of the migration of Midwestern farmers in previous decades, the

tropical climate of the Valley became widely known amongst their

families and friends. Wanting to escape the frigid Northern Winters

these friends and relatives came to visit once the weather started

turning cold in their northern homelands. Commonly referred to as

"snowbirds" they came in increasing numbers year after year. Hotels and

motels sprung up across the Valley to accommodate these winter

visitors. With the rise in popularity of traveling in recreational

vehicles came the development of campgrounds, RV parks and mobile home

resorts. Somewhere along the line, the term "snowbirds" was replaced by

the more affectionate term

"Winter Texans"

as they are known today. It is estimated that between 100,000 and

150,000 Winter Texans call the Valley their home for the winter every

year.

June 2014 ...

A Rich and Diverse Cultural History

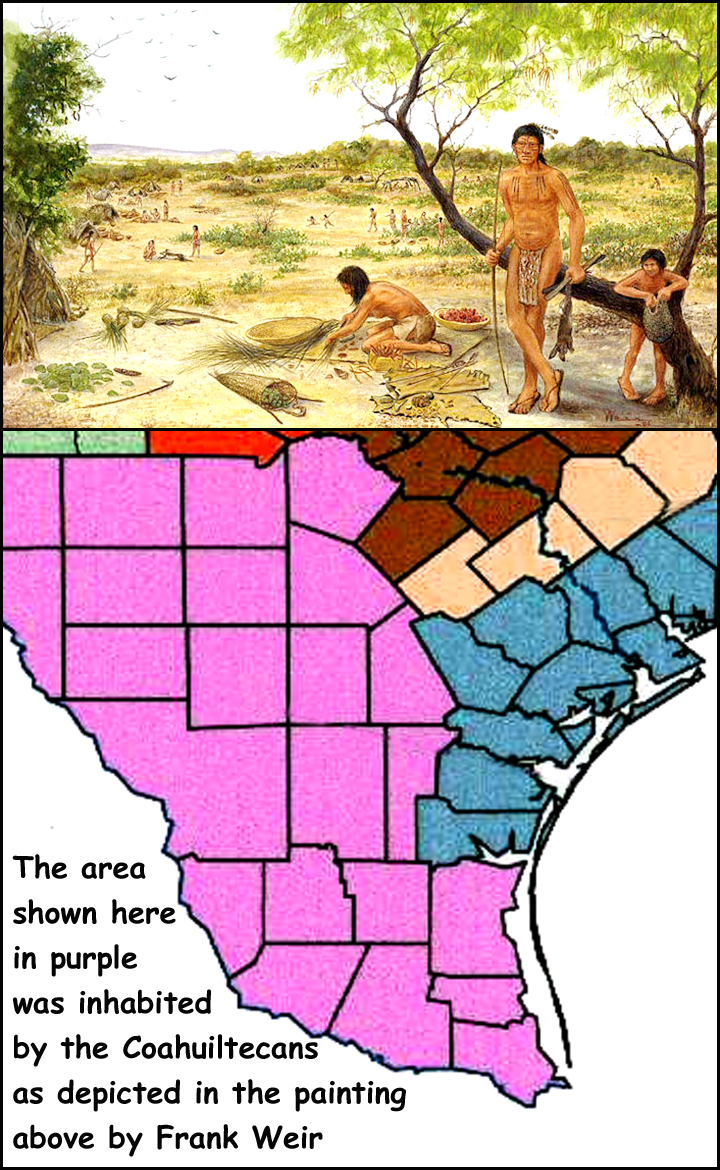

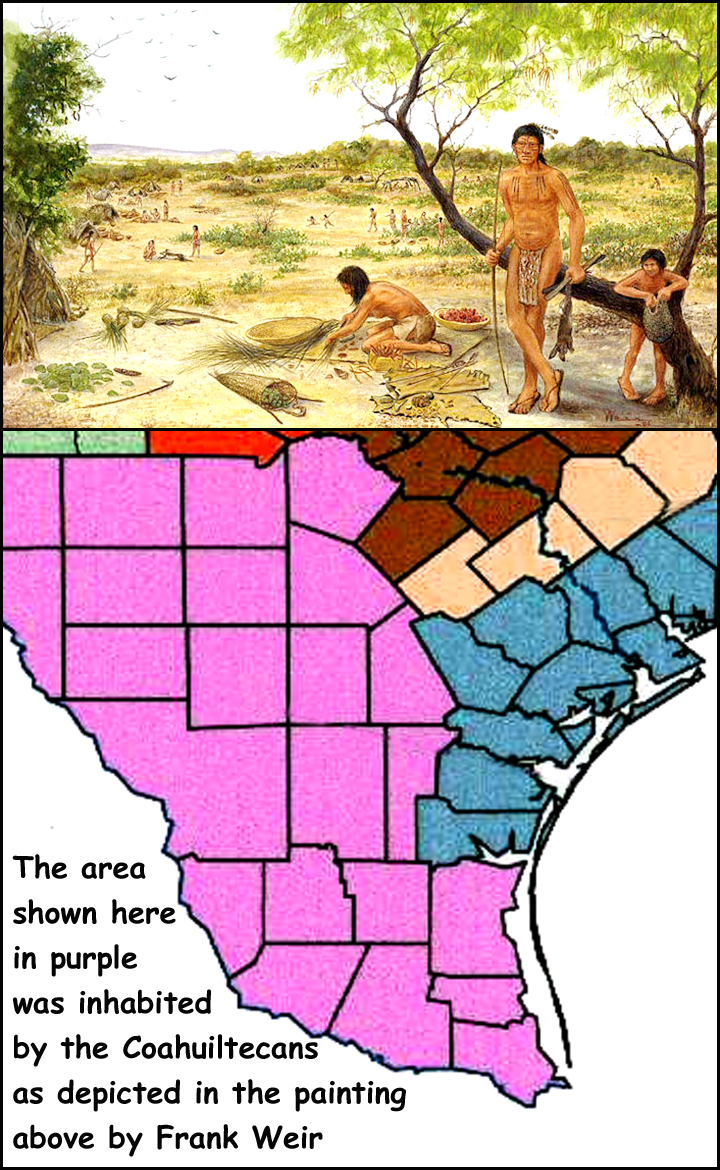

It is widely believed that Native Americans

have resided in South Texas for at

least 11,000 years.

These early inhabitants were hunters and

gatherers as evidenced by artifacts found

dating to the Archaic Period. Eventually,

some forms of agriculture, such as raising

maize, was introduced and thus began

the agricultural growth of the area.

In the 16th century, as Spanish explorers

began venturing into the area,the history

of the South Texas Plains began to

be recorded in written form.

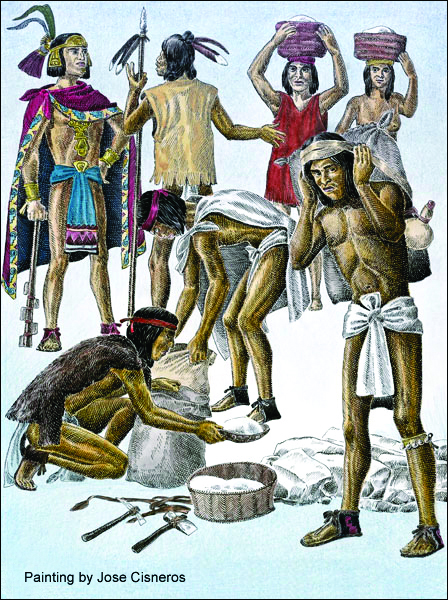

At this time hundreds of small, mobile

groups of hunter / gatherers spread

across southern Texas and northeastern

Mexico. These groups have collectively

become known as Coahuiltecans, however

individual tribes went by the names

of Payaya, Pacuache, Mariames and

dozens of others whose names have been

lost to history. These tribes spoke in a

vairety of dialects somewhat related to

each other such as Comecrudo, Cotoname,

Aranama, Solano, Sanan, as well

as Coahuilteco. Sharing overlapping territories,

particularly in the prickly pear

season, many of these tribes co-existed

peacefully.

Others were sworn enemies

of one another or simply had such widely

separated territories that they rarely

came in contact with each other.

The Coahuiltecans hunted a wide variety

of animals, fished, gathered berries,

fruits, and roots. During the Summer a

major food source for them were "tunas",

the tasty and nutritious fruit of

prickly pear cactus found in abundance

in this region.

La Sal del Rey, located in north-central

Hidalgo County, is one of several natural

salt lakes on the coastal plain north

of the Rio Grande.

Throughout historic

times and likely throughout prehistory

as well, the crystal-covered shores of

La Sal del Rey attracted both people

and animals.

An important mineral for

human nutrition, salt was also a critical

ingredient for preserving meat and

animal hides. Early inhabitants of South

Texas obtained salt for their own uses,

and possibly for trade as well.

Prehistoric trade in the lower Rio Grande

region is evidenced by pottery shards found at occupation sites near

Brownsville, which originated in the Huastec culture area on Mexico's

Gulf Coast

near Vera Cruz.

Shell ornaments characteristic

of the peoples near the Gulf coast

(the "Brownsville Complex") occur

at sites well inland, including Hidalgo

County. Salt may well have been a factor

in these trading activities. In addition,

local lore maintains that Indians from

the Mexican interior, including Aztecs,

obtained salt from La Sal del Rey.

Accounts of Aztec trade with northern

regions, as told in Spanish writings, may

lend credence to this tradition. More tangible

are obsidian artifacts found in the

Valley, their origins have been traced as

far away as central Mexico, indicating

definite links with that region.

Beginning in the 16th century Spanish

explorers traveled north from Mexico.

Searching for gold, these Spaniards traveled

first into what is now New Mexico

and then made their way along the Rio

Grande River into South Texas.

Watch for next month's issue

to read about the influence of

Spanish exploration on the

early history of the Rio Grande Valley.

July 2014 ...

Early Exploration of South Texas

"Difficult and Dangerous"

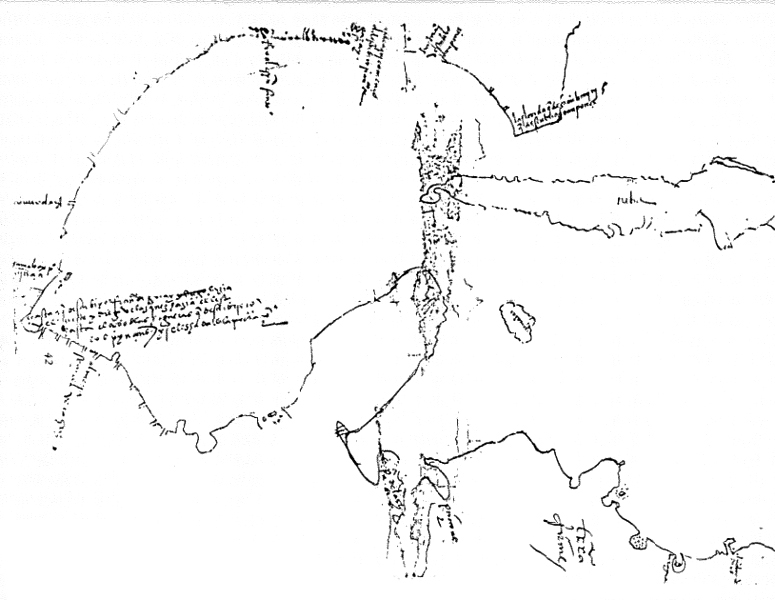

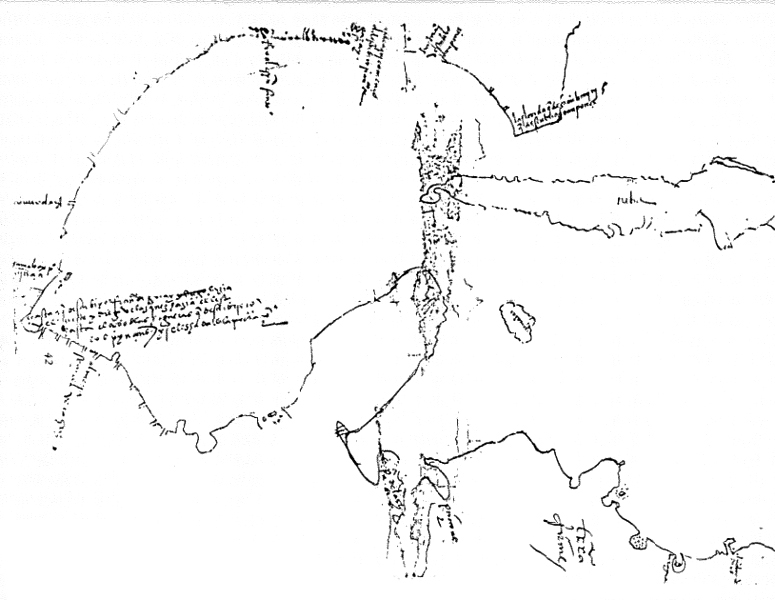

Francisco de Garay, a fellow spaniard, traveled with Christopher Columbus

on his second voyage to the "New World" in 1493. In 1514 he was

appointed as govenor of Jamaica by Spain's King Ferdinand. In 1519

Garay outfitted four ships to explore the northern Gulf shore and placed

them under the command of Alonso Alvarez de Pineda. Pineda and his

men were the first Europeans to explore and map the Gulf of Mexico

shorline from Florida to South Texas.

In 1527 Spain sent an expedition led by Panfilo de Narvaez in an attempt

to colonize "Spanish Florida". The expedition failed after the initial 600

men were reduced to only about 250 by hurricanes, attacks by indians,

poor food and disease. In September of 1528 these 250 "survivors"

sailed westward on crude rafts along the gulf coast. Storms and strong

currents swept several of the rafts out to sea, including Narvaez's, where

they were permanently lost. Cabeza de Vaca, the remaining captain, and

about 90 others continued along the coastline until they were eventually

shipwrecked on what is today Galveston Island.

Here they established a temporary encampment but soon found themselves

decimated by sickness and attacks from local indians. By the spring of

1529 there numbers had dwindled to about fifteen. A dozen of these

explorers left Cabeza de Vaca and headed south toward Mexico.

Nine of them died from mishaps and indian attacks leaving only

Alonso del Castillo, Andres Dorantes de Carranza, and his slave, the

African Estevanico who survived by becoming slaves of Coahuiltecan

Indians, the Mariames and Yguaces.

Meanwhile, Cabeza de Vaca and his two remaining countrymen explored

inland from Galveston Island. Passing from tribe to tribe for up to

3 years, Cabeza de Vaca developed sympathies for the indigenous

population.

He became a trader, which allowed him freedom to travel

among the tribes. Cabeza de Vaca claimed that he was guided by God

to learn to heal the sick and gained such notoriety as a faith healer

that

he and his companions gathered a

large following of natives who regarded

them as "children of the sun", endowed with the power to both heal

and destroy. Many natives accompanied

the men across what is now the

American Southwest and Northern

Mexico. An astonishing turn of fate

re-united Vaca with

the three survivors who had been enslaved by the local indian tribes

when he met a tribe known as the Quevenes at Matagorda Bay in 1532.

Unfortunatley for Cabeza de Vaca, he

now also was enslaved by the Mariames

indians.

When an opportunity for escape presented itself in late summer 1534

they headed south toward the Rio Grande River. It was their good luck

to be accepted by friendly Avavares Indians who ranged southwest of

Corpus Christi Bay. They remained with these natives for eight months

before leaving them in late spring 1535 and crossing the Rio Grande

into Mexico near the present-day International Falcon Reservoir.

These "ragged castaways" as they were later called, made their way along the

Rio Grande River to what is now El Paso where they tuned southward

and eventually arrived in Mexico City in July 1536.

In all they had walked on bare feet an estimated 2,400 miles from where

they had fled the Mariames and Yguaces in Texas.

August 2014 ...

Spain Ignores Texas Until Threatened by French Colonization in the Territory

As a result of the fact that no vast riches were

discovered in the area of New Spain which is

modern day Texas, the spanish royalty ignored

texas until 1685 when the French explorer

Robert Cavelier de La Salle established Ft. St.

Louis in what is now Victoria County, Texas.

Spain's King Carlos II, perceived the French

colony as a threat to Spain's claims in the territory

and launched 10 expeditions trying to locate

Ft. St. Louis.

In 1689 the Spanish explorer

Alonso de Leon finally discovered the remains

of the French colony which had lasted only

3 years due to epidemics, indian attacks and

harsh conditions. Years later, Spanish authorities

built a presidio at the same location. When

the Spanish presidio was abandoned, the site of

the French settlement was forgotten to history.

The importance of these spanish expeditions

lies in the fact that De Leon sent a report of his

findings to Mexico City, where it created instant

optimism and quickened religious fervor.

The Spanish government was convinced that

the destruction of the French fort was "proof

of God's 'divine aid and favor'". In his report

de Leon recommended that presidios be established

along the Rio Grande, the Frio River,

and the Guadalupe River and that missions be

established among the Hasinai Indians, whom

the Spanish called the Tejas.

Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza approved the

establishment of a mission but rejected the idea

of presidios (fortified bases).

On March 26, 1690, Alonso de Leon set out

with 110 soldiers and several missionaries and

established Mission San Francisco de los Tejas

near the eastern Texas Hasinai village of

Nabedaches in late May.

Smallpox epidemics, drought and hostilities with the local indians

caused this mission to be abandoned in 1693.

After several failed attempts to re-establish

the mission it was relocated to the area which is

now San Antonio and was renamed San Francisco

de la Espada. Many Spanish missions were established in

what is presently Central and East Texas during

the late 1600s and early 1700s.

Mission San Antonio de Valero was established

on May 1, 1718 as the first Spanish mission

along the San Antonio River. It was named

for San Antonio de Padua, the patron saint of

the mission's founder, Father Antonio de Olivares

as well as the viceroy of New Spain, the

Marquis de Valero. This is the mission that later

became known as the Alamo.

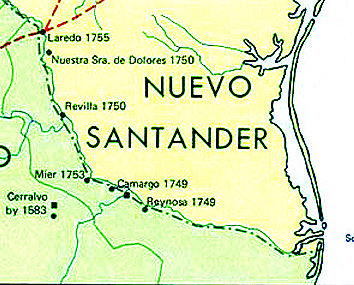

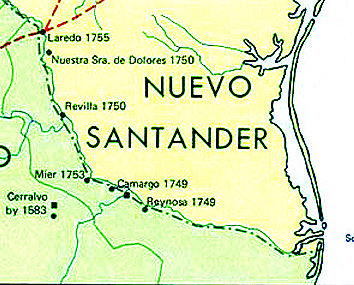

In 1749, in a major colonizing effort along

the Rio Grande, four towns were founded on

the south bank of the river in Mexico: Reynosa,

Camargo, Mier and Revilla (now Guerrero).

Some time later, the missions in these settlements

all established outposts on the Texas side

when some of the settlers began to move across

the river. These outposts were visitas and took

their names from those missions.

A visita was

a kind of country chapel that was visited by the

priests for Mass or to administer sacraments.

One of these visitas was in Zapata County. It was an outpost of the Mission San Francisco

Solano de Ampuero that was in the Mexican

town of Revilla. Called Mission Revilla a Visita,

it is commemorated with a state historical

marker in the present-day city of Zapata at the

courthouse plaza.

Also in Zapata County was the ranch settlement

of Nuestra Senora de los Dolores, established

in 1750, about 11 miles north of San Ygnacio.

Today, the site is referred to as Dolores

Hacienda. Although a state historical marker

put up by the Texas Centennial Commission in

1936 says there was a mission there, later research

indicates there was only a small chapel

for religious services provided by priests from

Revilla.

In 1755, another ranch settlement was founded

on the east bank of the river at Laredo. Until

1760, when it received its first resident secular

priest, Franciscan friars from the Revilla mission

visited Laredo on occasion to minister to

the settlers.

The Mexican city of Mier was the site of the

mission La Purisima Concepcion, and across

the river in present-day Starr County was Mission

Mier a Visita, begun sometime in the mid-

1750s. There is a state historical marker on US

83, 3.5 miles west of Roma.

At the same time,

another visita was established from San Agustin

de Laredo mission in Camargo, Mexico.

There is a state historical marker 2.5 miles west

of Rio Grande City on US 83.

Farther south in Hidalgo County a visita was

established in the mid-1750s from the mission

San Joaquin del Monte in Reynosa. A marker

in McAllen Park in Hidalgo commemorates the

visita.

September 2014 ...

Early Colonization of Spanish Texas

By the end of the 18th century there were

about 3,500 spanish colonists in the area

known as Spanish Texas. Many of the settlers

were former soldiers who had been

stationed at the various presidios during

the time that missions were being established.

Others were immigrants brought by

the Spanish government from the Canary

Islands and there were the missionaries

who had come in the early 1700s to spread

Christianity among the native Indians.

Life was particularly difficult and dangerous

during this period of Texas history.

While some native tribes of Indians accepted

the Spanish and co-existed peacefully,

there were others who did not take kindly

to the Spaniards efforts to force their way of

life upon them.

To make matters worse, the westward

expansion of American pioneers forced

Indian tribes such as the Apaches and the

Comanches to migrate into Spanish Texas.

Because these two tribes were constantly

warring with each other, their presence in

Texas caused hardships for the Spanish settlers

as well as the native tribes of the area.

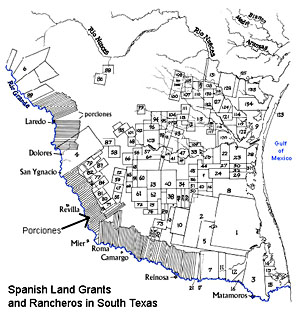

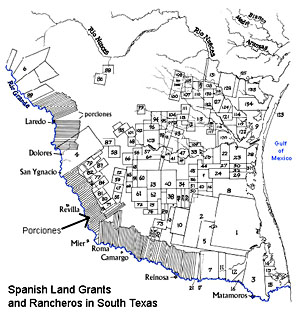

It was during this tumultuous time that the

Spanish government awarded land grants in

the area known then as Nuevo Santander.

The land was divided on the basis of merit

and seniority. Due to the shortage of water

sources, porciones were long narrow strips

of land bordering the river.

These porciones were a little over a half mile wide and about

12 miles deep.

Families were also given a

small plot in town to build a house, if they

wished. Many of the buildings on each porcion

were placed near the Rio Grande, just

far enough away to avoid flooding, and the

rest of the land was used for sheep, goats,

and cattle.

Larger grants were made at the back of

the porciones or along the Gulf of Mexico

which went to influential citizens of Camargo

and Reynosa. These land grants were

several hundred thousand acres in size. At

this time the landscape consisted of grassy

plains with brushy areas concentrated near

waterways. These large land grants were

used mainly for cattle ranching.

No fences were used, and the animals

could roam as they pleased across boundaries.

Mesquite trees became more abundant

in the region as a result of these free roaming

cattle. Cattle belonging to different owners

would often merge together into large

herds, and would only be separated during

a rodeo, or roundup. Over time, these wild

herds of cattle would evolve into the Texas Longhorn so familiar today.

Protection from Indian and Bandit raids

against these ranchos was provided by the

Spanish military based in the villas along

the Rio Grande River.

In 1951, archeologists from the University

of Texas excavated several sites along the

Rio Grande River in advance of construction

crews who were to build Falcon Dam

near present day Zapata. Below are some

artifacts that were discovered during these

excavations.

A Local Resident's Connection to the Past

Gordon Jenkins, a present day

resident of the RGV, traces his

family's heritage back to the land

grants of the 1700s.

He tells the story of his ancestors,

the Cardenas family, who

acquired the land grant called San

Salvador del Tule near what is today,

Edinburg.

This land grant consisted of over

300,000 acres. Included within it's

boundaries is the salt lake known

as "Sal del Rey", a revenue source

for the Spanish Crown since it imposed

a one-fifth tax on the salt

that was sold.

Antonio Cardenas, a prominent

citizen of Reynosa, had an interest

in the land and so did Capt. Jose

Maria Balli an officer of the Spanish

military posted in Reynosa.

However, Cardenas elected not

to bid against Capt. Balli for the

land grant because he realized that

the Spanish soldiers from Reynosa

provided the only protection

against Indian and Bandit raids on

the frontier ranchos.

The Tule lands were granted to

Capt. Balli's son Juan Jose Balli

in 1798. Balli obtained a business

loan from the Cardenas family

to develop the land. Balli was

charged by Spanish officials with

smuggling salt from El Sal del Rey

and not paying the King's tax. He was also suspected of aiding the

cause of Mexican independence

from Spain.

He was imprisoned in 1804 at

Altamira prison in San Carlos,

Mexico, and died there on May 9

of that year. San Salvador del Tule

was passed to his heirs.

In 1829 members of the Cardenas

family demanded payment on

the loan that was given to the Ballis

back in 1798. In lieu of payment

the Balli family gave the San Salvador

del Tule land to the Cardenas

family who then established

La Noria Cardenena Ranch. Ranch

headquarters was on the Old Salt

Road from the historic royal salt

lake, El Sal del Rey, which was

part of the ranch, to Cerralvo.

Cardenas and Cavazos families,

who owned adjacent land, were

united by the marriage of Amado

Cavazos and Manuela Cardenas

in 1862. There followed many

other marriages between the two

families. Together they built a

strong cattle-ranching community,

which became the hub of over 40

ranches. During the Civil War, the

Cardenas family fled to Mexico.

The Confederate government of

Texas seized El Sal del Rey for its

valuable salt. After 80 years of litigation,

the Cardenas family recovered

parts of San Salvador del Tule

in a landmark decision involving

sovereign mineral rights.

The two families have held reunions

since 1913. The main

ranchhouse built in 1855-1865 still

stands.

October 2014 ...

Transition From Spanish Texas to Mexican Texas

By the late 1700s a nice little society

was growing in Nuevo Santander (present

day Texas). But the people were

beginning to feel far removed from the

King in Spain.

Without offering much support, Spain

taxed the colonies, cut off funding to

the missions and strictly enforced laws

which the colonists believed to be unfair.

Further south in New Spain, tensions

were developing between Spaniards

born in Spain, known as peninsulares

and Criollos, locally born citizens of

pure Spanish descent.

Spurred by the defeat of Spain by Napoleon

in 1808 the peninsulares took

control of the local government of New

Spain. Criollos supported by the Indians

and mestizos (people of Indian and

Spanish blood), conspired against this

new ruling class and began the fight for

Mexican Independence.

After more than a decade of bloody

war, independence was won in 1821

and the territory was given the name of

Mexico after its capitol, Mexico City.

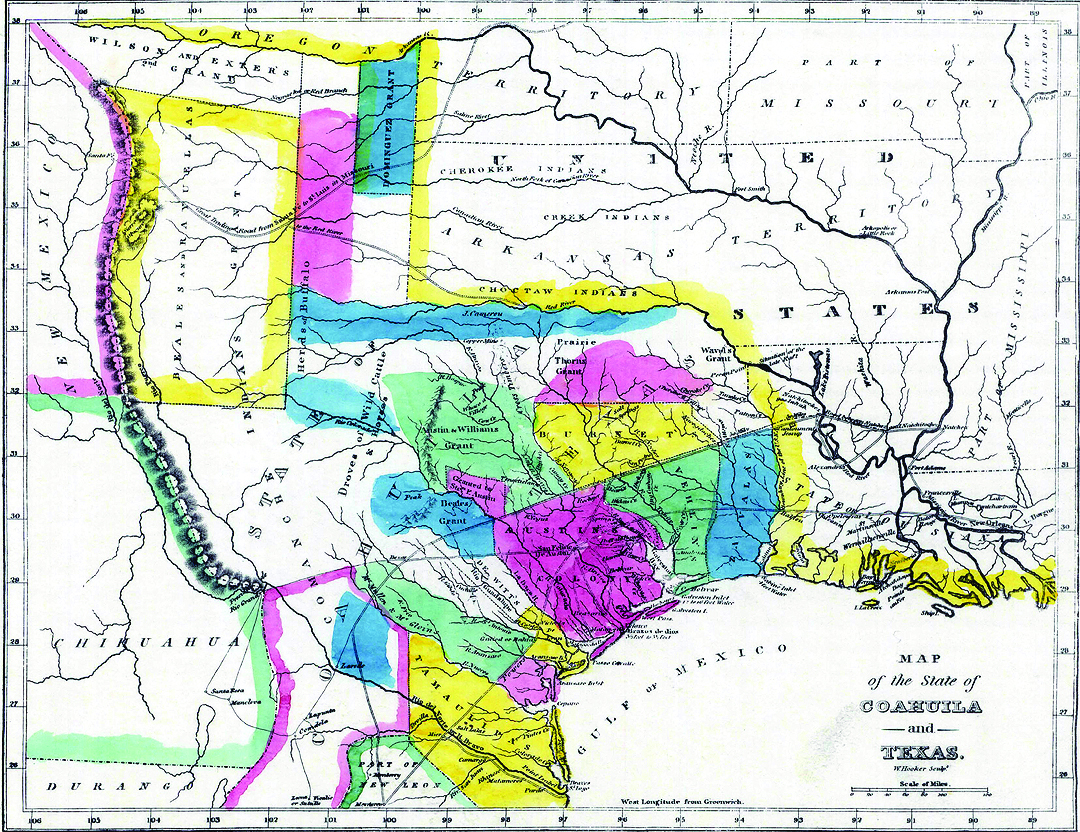

Having been illegal under Spanish rule

until 1820, Anglo-American immigration

into Nuevo Santander was expanded

by Mexico's National Colonization

Law of August 18, 1824. However, this

law favored Mexican immigrants from

the south, soldiers and nomadic Texas

tribes by giving them priority in acquiring

land. Between 1821 and 1835, forty-

one land contracts permitted 13,500

families, mostly Anglo-Americans, to

settle in Texas.

Anglo-Americans were attracted to

Mexican Texas because of undeveloped

land which could be purchased for $1.25

an acre for a minimum of 80 acres. Each

head of a family, male or female, could

claim a headright of 4,605 acres (one

league-4,428 acres of grazing land and

one labor-177 acres of irrigable farm

land) at a cost about four cents an acre

($184) payable in six years.

Stephen F. Austin received one of the

first grants to establish a colony in Texas

on August 1823 on land acquired by

his father, Moses Austin, from Spain in

1820. Two thousand settlers settled in

the new colony that stretched from the

east coast of Texas to La Grange.

By 1834, over 30,000 Anglos lived in

Texas, compared to 7,800 Mexicans.

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna became

the president of Mexico in 1833. In

1835 he dissolved the Congress and his

regime became a dictatorship backed by

the military.

November 2014 ...

The Rio Grande Valley During

The Texas Revolution and The Mexican American War

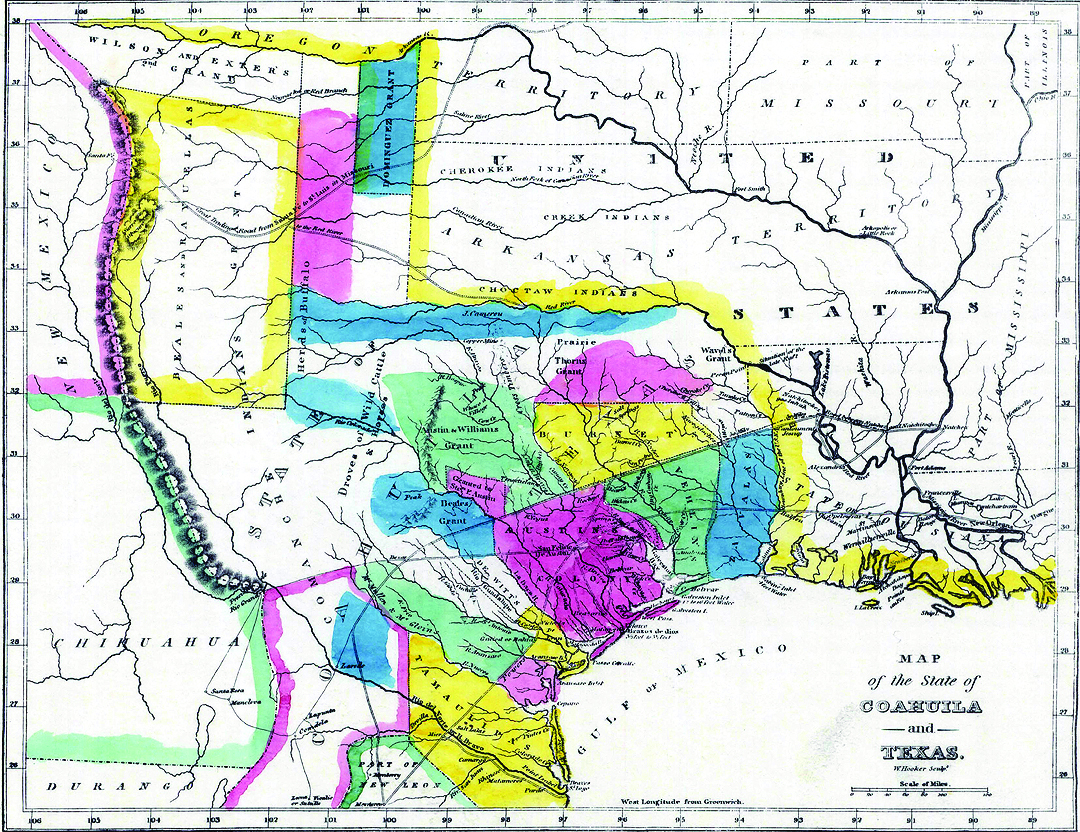

Following the Mexican War of Independence

the Rio Grande Valley was part of Coahuila y

Tejas which was formed through the United

Mexican States 1824 Constitution.

Matamoros and Reynosa had been established

south of the Rio Grande River but were

little more than sleepy border towns.

The area north of the river was a sparsley

populated area inhabited by settlers of these

towns. The territory, having been divided into

porciones and land grants, was primarily used

for ranching and consisted of vast areas of

grasslands with woody areas located around

sources of water near the river.

Cattle raising was successfully established in

the area despite hardships caused by flooding

and Indian raids.

In the 1820s, early Anglo-American settlers

led by Stephen F. Austin colonized Texas in areas

north of the Colorado River between San

Antonio and the Eastern border with Louisiana.

The Mexican government tried unsuccessfully

to encourage Mexican citizens to settle in Texas

and the Anglo-American settlers soon out

numbered Mexicans nearly four to one. Fearing

annexation of Texas by the United States, the

Mexican government banned further immigration

from the US in 1830. This action is said to

be one of the main factors in causing Texas to

revolt and seek independence from Mexico.

Like other Mexican states discontented with

the central Mexican authorities, the Texas department

of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas

rebelled in late 1835 and declared itself independent

on 2 March 1836. Santa Anna marched

north to bring Texas back under Mexican control

by a show of brute merciless force. Santa

Anna's force crossed the Rio Grande above Laredo

on February 16, 1836. A second Mexican

force, led by Gen. Jose de Urrea, crossed the Rio

Grande at Matamoros the next day.

Major battles in the war for Texas' independence

took place in the territory from San Antonio

to the Eastern border, however there was

some action in the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

The Matamoros Expedition

In February of 1836 Colonel James Fannin led

a force of around 200 men on an ill fated attempt

to attack Matamoros to prevent it from

being used as a staging point for the Mexican

army. Unfortunately, escaped Mexican prisoners

were able to warn Gen. Urrea of the plan.

Urrea's army marched north and defeated Fannin's

forces at Goliad, executing 342 prisoners

of war under the direct order of Santa Ana.

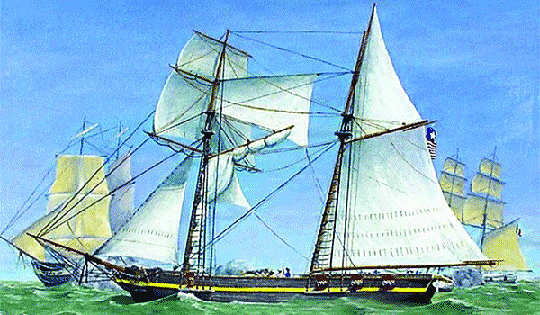

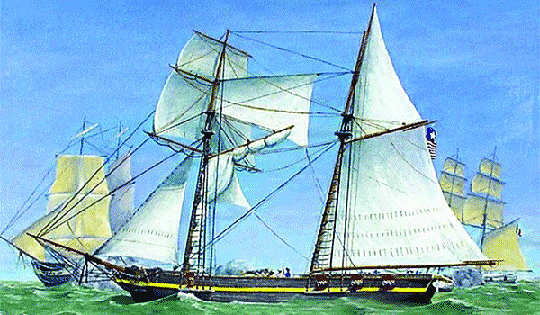

The Texas Navy

In November 1835 the provisional government

of Texas established an official navy. In

January 1836, agents purchased four schooners:

Invincible, Brutus, Independence, and Liberty.

According to Teddy Roosevelt, the Texas Navy succeeded

in preventing reinforcements and provisions at the Mexican

naval base at Matamoros from reaching General

Santa Anna's forces then occupying Texas.

This forced Santa Anna to disperse his large

army, to forage for food and supplies and in

turn led to his defeat at San Jacinto by General

Sam Houston in April, 1836 and the signing of

the Treaties of Velasco.

The Mexican government's refusal to acknowledge

the Treaties of Velasco eventually

led to the Mexican American War following

the annexation of Texas by the United States

in 1845.

The United States claimed Texas' southern

border to be the Rio Grande River while Mexico

saw it as ending at the Nueces River.

After a declaration of war on May 13, 1846 US

forces invaded Mexican territory on two main

fronts. The US War Department sent a US cavalry

force under Stephen W. Kearny to invade

western Mexico from Jefferson Barracks and

Fort Leavenworth, reinforced by a Pacific fleet

under John D. Sloat. This was done primarily

because of concerns that Britain might also try

to seize the area. Two more forces, one under

John E. Wool and the other under Taylor, successfully

occupied major cities in Mexico as far

south as the city of Monterrey.

Military conflicts in the Lower Rio Grande

Valley during the Mexican American War include

the Siege of Fort Brown, in Brownsville

and the battles of Palto Alto and Resaca de la

Palma.

Outnumbered militarily and with many of

its large cities occupied, Mexico could not defend

itself and signed the Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. The treaty gave

the US undisputed control of Texas firmly establishing

the US-Mexican border as the Rio

Grande River.

December 2014 ...

The Civil War Era in the RGV

After the end of the Mexican-American

War the population of Texas grew rapidly

as migrants poured into the cotton

lands of the state. In addition to Americans

moving into Texas, thousands immigrated

from Germany and Czechoslovakia.

Cotton plantations brought with them

slavery, and in 1860, 30% of the total

state's population of 604,215 were

slaves. Texas declared its secession

from the United States on February 1,

1861, and joined the Confederate States

of America on March 2, 1861.

It is estimated that in 1861 only one

third of the white population in Texas

supported the Confederacy.

Those loyal to the Union were mainly from the northern counties, the German districts and the Mexican areas. Large

scale massacres against these unionists

caused many to flee south across the Rio

Grande River into Mexico.

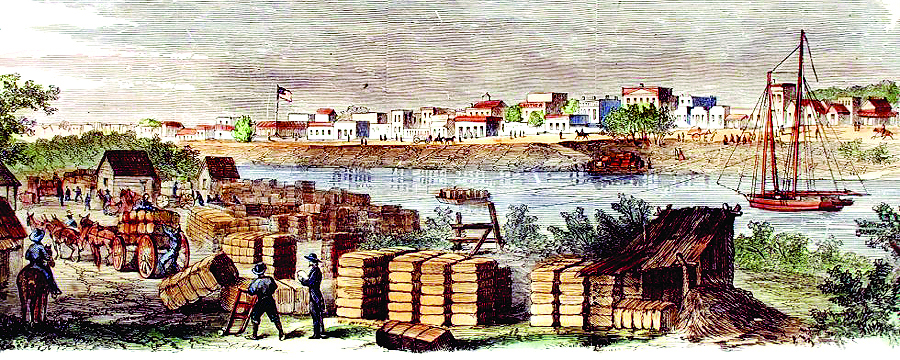

During the Civil War, the Rio Grande

River delta was a vital depot for the

Confederate cotton trade.

With Union ships blockading ports from Virginia to

Texas, Confederate leaders transported

their "white gold" across the Rio

Grande, loaded it onto Mexican flagships

in the Port of Bagdad and sailed

it safely past the blockading forces.

Fort Brown, in Brownsville, became a

strategic location for this thriving trade.

In November 1863, Union troops

invaded Texas at Brazos Island and

marched inland successfully occupying

Brownsville in an attempt to halt

the flow of cotton. They held the territory

until July 1864 when Confederate

troops recaptured the city. Union forces

were forced to withdraw to Brazos Island

where they remained stationed for

the remainder of the war.

Few battles actually took place in

Texas during the civil war. However, the

Rio Grande Valley is the site of the last

battle of the war. The Battle of Palmito

Ranch was fought in May 1865, one

month after the surrender of Confederate

Gen. Robert E. Lee in April 1865. Ironically,

the Confederate troops claimed a

victory in this the final conflict of the

Civil War.

The Lost Cities of the Rio Grande Valley

The Port of Bagdad

Bagdad, Tamaulipas, Mexico

was a town established in 1848 on

the south bank of the mouth of the

Rio Grande River inside the municipality

of Matamoros. In 1861

Matamoros had a population of

about 40,000 and the Port of Bagdad

population was nearly 12,000.

Prior to the American Civil War,

Bagdad was but a recreational

destination for the residents of

Matamoros. When the Mexican-

American War broke out, Matamoros

was split into two cities.

Those residents with loyalties to

the United States moved north of

the Rio Bravo (the Rio Grande)

and created Brownsville. However,

Bagdad continued on as a destination

for recreation for the people

of both cities.

During the American Civil War,

Union warships bottled up Southern

ports. In response, the Confederacy opened a back door on the

Rio Grande River, which by treaty

was an international waterway.

Cotton was the "white gold" that

would sustain the Confederacy

during the Civil War, and cotton

was literally "King" in south

Texas.

Richard King, owner of

the famed King Ranch, along with

several partners, was a major player

in the cotton trade during this

time period.

Cotton was hauled by wagon,

oxcart and mule cart to Matamoros

where many speculators and

agents vied for this valuable commodity

to ship to Europe. They

offered in exchange vital goods:

guns, ammunition, drugs, shoes &

cloth. At Bagdad, cotton was loaded

from small boats onto ships in

the Gulf of Mexico. Goods crossing

here played an important role

in the South's war effort.

Clarksville

Clarksville, Texas was near the

mouth of the Rio Grande, opposite

the Mexican city of Bagdad. During

the Mexican War a temporary

army camp stood there, with William

H. Clark, a civilian, in charge.

Clark set up a country store and

served as agent for the steamship

lines using the port. The town

quickly developed; houses were

built up on stilts to be above high

water. During the early part of the

Civil War Clarksville thrived on

the trade of the Confederate blockade-

runners, but in 1863 it was

captured by federals, who held it

most of the time until the end of

the war.

Brazos Santiago

The Port of Brazos Santiago was

located on Brazos Island in what is

now Cameron County, across Brazos

Santiago Pass from the south

end of Padre Island.

By 1867 the north end of Brazos

Island was a well-developed

military port with three wharves

on Brazos Santiago Pass, a railroad

south to Boca Chica and on to

Whites Ranch on the Rio Grande,

four barracks, a hospital with four

outbuildings, two gun emplacements,

numerous warehouse buildings,

and a lighthouse. After the

Civil War the troops left Brazos Island,

and the small town of Brazos

faded away.

Natures Fury

Natures Fury

On October 7, 1867 an intense hurricane struck the mouth of the Rio

Grande with great fury and devastated the towns of Clarksville, Texas,

Brazos Santiago, Texas and Bagdad, Tamaulipas, Mexico. In 1874, another

storm roared ashore at the mouth of the Rio Grande River. A storm

surge of over twenty feet inundated much of the shore from the mouth

of the river north. These natural disasters spelled the end of the Lost Cities

of The Rio Grande Valley and very little physical evidence remains

today to prove their existence.

January 2015 ...

Early Development of the Rio Grande Valley as an Agricultural Center

The lower Rio Grande contains

good agricultural land, the region

being a true delta and the soil varying

from sandy and silty loam

through loam to clay. The area of

about 43,000 square miles witnessed

a tremendous development

in a period of about thirty years

from the late 1800s to through the

early 1900s.

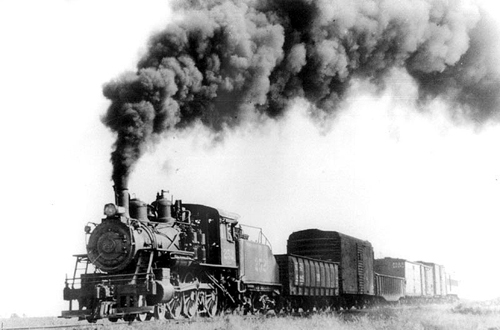

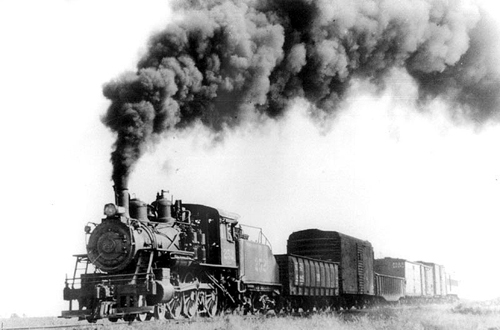

This spectacular development is

attributable to two factors: the introduction

of irrigation on a large

scale in 1898 and the building of

the railroad in 1904.

Before that time the Valley was

little more than quasi-desert rangeland.

When the Spanish first occupied

the area around 1750, they

settled on the right bank of the river

and divided the area north of the

river into great cattle-ranch grants.

The first American settlement in

the area was Brownsville, which was founded as a result of the invasion

of Zachary Taylor and the

United States Army in the Mexican

War (1846). The town, which

sprang up around Fort Brown, remained

practically the only settlement

of size or distinction in the

Valley for over half a century.

The coming of the railroad and irrigation

made the Valley into a major

agricultural center. In Hidalgo

County, land that had been selling

for 25 cents an acre in 1903, the year

before the St. Louis, Brownsville

and Mexico Railway arrived, was

selling for $50 an acre in 1906

and for as much as $300 an acre

by 1910.

A large-scale migration

of midwestern farmers in the teens

and twenties, matched by a growing

surge of Mexican immigration

during the same period, led to dramatic

population growth in Valley

counties.

The population of Cameron County

grew from just over 16,000 in

1900 to 77,540 in 1930; that of Hidalgo

County climbed from 6,534

in 1900 to 38,110 in 1920 and just

over 77,000 in 1930. By 1930 the

population of the four lower Rio

Grande valley counties exceeded

176,000.

After the arrival of the railroad in

1905 the town of McAllen began

developing. With the introduction

of an irrigation system vegetable

farming was now possible. The

Valley became a truck garden center

for tomatoes, cabbage, carrots,

potatoes, beets, corn, green beans,

and onions.

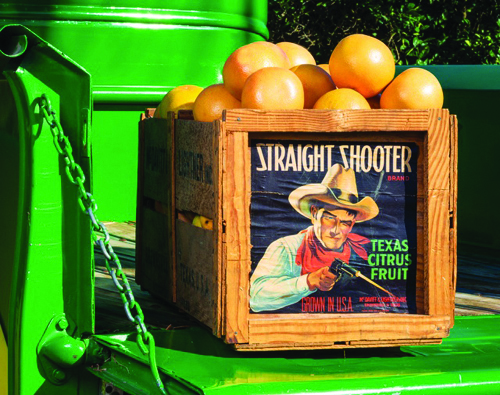

Cotton and sorghum became important

staples early on, but the

most important crop in the region

is citrus fruit.

Introduced commercially in the

region in 1904, citrus fruit culture has survived severe freezes in

1949, 1951, 1961, 1983 and 1989.

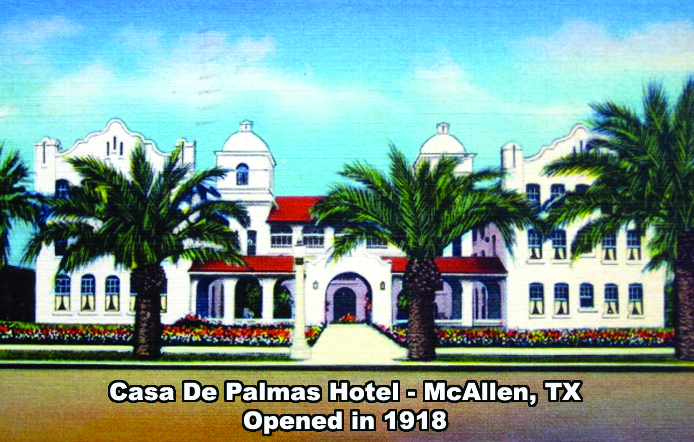

Soon McAllen had a hotel, a grocery

store, a Presbyterian church, a

bank, and a weekly newspaper. In

1916 after bandits caused border

trouble 12,000 soldiers were sent

here to restore law and order. Business

boomed with the increased

population.

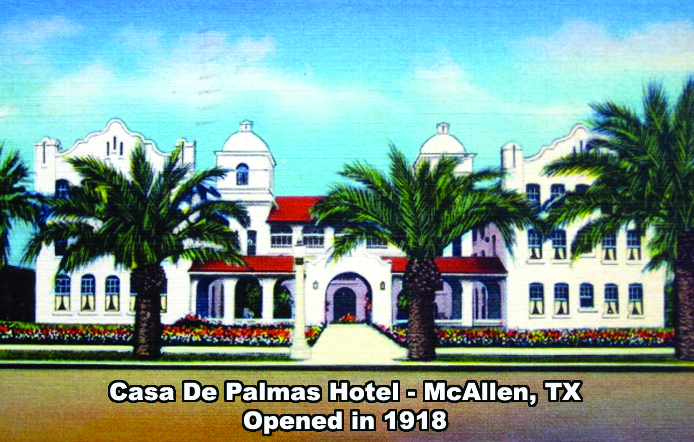

The Casa de Palmas Hotel, opened

in 1918 and served as a business,

social, and civic center for the Rio

Grande Valley.

February 2015 ...

THE "MAGIC VALLEY"

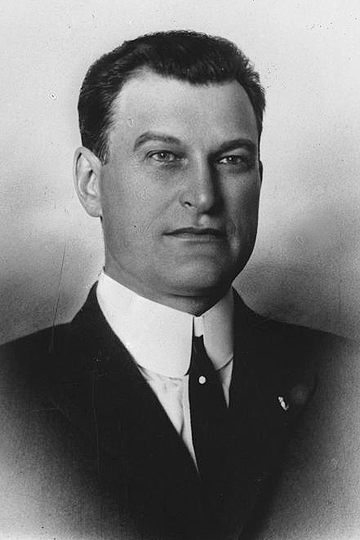

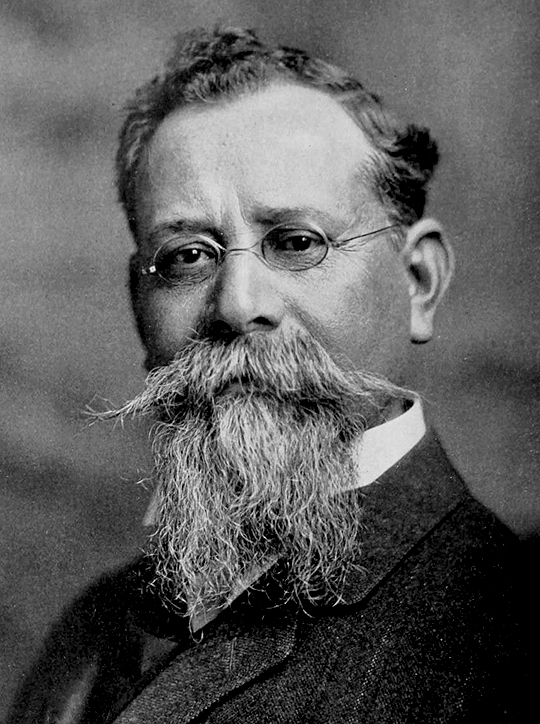

When it comes to understanding how

the Rio Grande Valley became The Magic

Valley, two pioneers stand in the forefront:

John H. Shary and Lloyd Millard

Bentsen, Sr.

John H. Shary

John Harry Shary, the son of Bohemian

immigrants was born on a Saline County,

Nebraska, farm on March 2, 1872. At

the age of 22, John joined a California

redwood lumber firm for which he traveled

throughout the United States and

in Canada.

He became

interested in

land investments

and development,

particularly in Texas.

Between 1906

and 1910 he and

George H. Paul developed

250,000

acres in the cotton producing

area around Corpus Christi,

operating from out-of-state offices with

special trains transporting prospective

buyers to South Texas on a weekly basis.

Impressed by the commercial potential

of citrus-growing experiments in the

lower Rio Grande Valley region John

Shary bought and subdivided more than

50,000 acres of land in the Valley and installed an irrigation system.

With the financial help of Jesse H.

Jones he bought most of the early experimental

citrus groves, especially grapefruit,

and from them he harvested some

of the early commercial citrus crops after

World War I.

John became very influential in the

Valley. He headed numerous commercial

firms, including banks, land companies,

and newspapers, and was a director of the

Intercoastal Canal Association and the

St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico Railway

Company. John and his wife Mary

lived on the Shary Estate in Sharyland,

northeast of Mission. They also maintained

homes in Omaha, Nebraska, and

Branson, Missouri, thus qualifying them

as what we today call "Winter Texans".

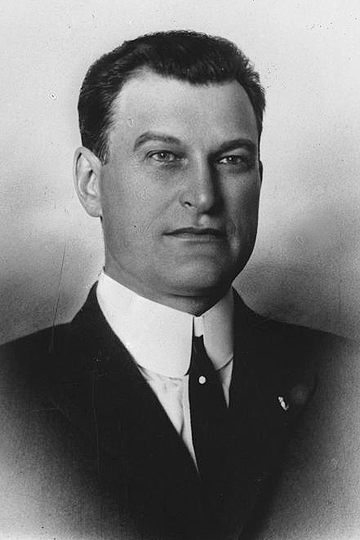

Lloyd M. Bentsen Sr.

Lloyd M. Bentsen Sr.

In 1918, heeding medical advice, Peter

and Tena Bentsen left their homestead

in Argo Township, South Dakota and

drove by car for 17 days and 1,675 miles

to Sharyland, Texas. They were accompanied

by their son Lloyd and his wife,

Dolly. Arriving penniless, Peter Bentsen

rented a place in Mission and began

working as a land agent for John Shary.

Lloyd and his brother Elmer Bentsen

became the premier colonizers and developers of Hidalgo County, which

led all counties of the United States in

cotton production and raised a good part

of the Valley's 1948 $100 million citrus

and vegetable crop. In 1952 the county

centennial program described the contribution

of Lloyd and Elmer's stake in the

county's economic development. The

Pride O Texas citrus trademark contributed

substantially to the fortune that the

Bentsen family began amassing.

Elmer and Lloyd were principals in the Elsa

State Bank, Elmer a president and director

and Lloyd on the board of directors.

Lloyd was also a principal in the First

National banks of McAllen, Mission,

Edinburg, Raymondville, and Brownsville.

He served as president of the Rio

Grande Valley Chamber of Commerce

from 1944 to 1946

and was instrumental

in uniting and

developing Cameron,

Hidalgo, Starr,

and Willacy counties.

Later in life he

became sensitive to

preserving the natural

environment of the Valley and donated

land that became the

Bentsen-Rio

Grande Valley State Scenic Park.

May 2015 ...

The Forgotten Americans ...

The Story of Rio Rico

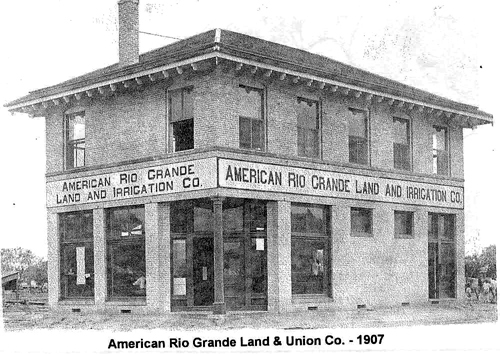

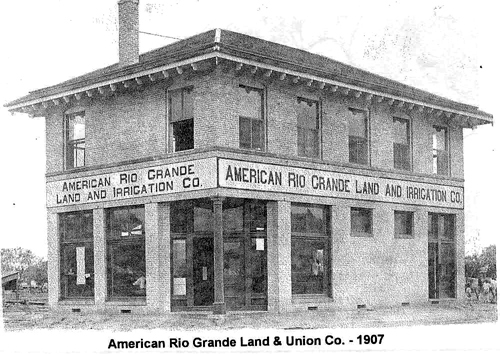

In 1906 the Rio Grande Land and Irrigation

Company owned the tract of land south

of Mercedes, TX which is now known as

the Horcon Tract. Located on this tract of

land was a small Texas town called Rio

Rico. Owners of the company were concerned

that the Rio Grande River, the official

boundary between Texas and Mexico,

would shift its course leaving their new irrigation

pumping station high and dry.

Without legal authorization, they diverted

the river's course manually by blasting and

digging a new channel north of the town of

Rio Rico. When all was said and done, Rio

Rico, TX was left south of the river.

American authorities charged the company

with violating treaties with Mexico that

forbade artificial water diversions. Those

treaties also stipulated that while such diversions

might change the course of the

river, they did not change the international

boundary. The company paid a $10,000 fine

in 1911, and also paid $2,000 to survey and

mark the international boundary in the nowdry

riverbed.

Even though the tract of land was legally

still a part of the United States, its location,

now south of the river, caused it to come

under the jurisdiction of Mexican authorities

in the area.

Local Texans paid little attention to this

situation. In fact the town of Rio Rico prospered

as a gambling community during the

prohibition years. A Chicago syndicate, rumored

to have ties to Al Capone himself,

developed Rio Rico in 1928. They built a

greyhound race track and saloons and welcomed

Texans to come and enjoy themselves.

Some say that they may have smuggled

narcotics out of Mexico by hiding the

drugs under the blankets placed over the

dogs after a race.

For 10 cents, anyone could cross a two

lane, 260-foot suspension bridge built in

1928 linking Rio Rico, on the south end of

the bridge, and Thayer, Texas.

"The story goes, in one year they paid back

the bridge completely on that 10-cent fee.

That's how many people went over there,"

said Laurier McDonald, retired Edinburg attorney and local historian.

The town's resort status plummeted at the

end of prohibition in the mid-1930s. When

a storm washed away the bridge in 1941,

the town became just another small border

town.

Legal Ramifications

When the Rio Grande Land and Irrigation

Company paid the fines imposed and the

cost of surveying the international boundary,

they neglected to pay an additional $200

to place markers defining those boundaries.

After prohibition was repealed Rio Rico

faded into the past and became just another

sleepy border town. Persistent flooding

caused residents of the town to relocate farther

south to where it is presently located.

Mexican authorities continued to govern

the area even though officially it was still in

United States territory.

For three decades Texans virtually ignored

Rio Rico as though it never existed. Then in

1967 James E. Hill Jr. was writing a scholarly

treatise and stumbled upon the forgotten

EI Horcon Tract. Calling the tax assessor

of Hidalgo County, Hill asked if they

were collecting taxes on the Texas land. He

was told they weren't since the county had

no control of Rio Rico because it was south

of the river, Mexico territory.

Though the residents of Rio Rico were

nicknamed the Lost Americans, the Forgotten

Americans, nothing more was done

until Homero Cantu Trevino entered the

picture, walking into the Edinburg, TX law office of Laurier McDonald to inquire about

immigration papers. As fate would have it,

McDonald had been talking to the County

Tax Assessor and knew of the stories of Rio

Rico and the Horcon Tract.

When Cantu stated his birthplace as Rio

Rico, McDonald's interest was piqued. "As

far as I'm concerned, based on what you

told me, you're an American citizen," McDonald told Cantu.

As a result of this chance encounter and

the litigation that followed, Cantu was declared

an American Citizen by Interim Decision

No. 2748 in Hidalgo County.

In 1970, the U.S. ceded the territory to

Mexico in the Boundary Treaty of 1970, the

American-Mexican Treaty Act of October

25, 1972 authorized the U.S.'s participation

and the handover to Mexico took place in

1977.

At the announcement of Rio Rico being

American soil from 1906 to 1972, Rio

Rico became a virtual ghost town overnight

as residents flocked to the U.S. to gain their

rightful citizenship. From around the world,

non-Americans called, claiming Rio Rico

as their birthplace hoping for that elusive

U.S. citizenship. McDonald helped over

250 claim their legal rights as Americans.

If only the land and irrigation company

had paid the $200 for those silly little markers,

copious amounts of time and money

would have been saved.

On a final note... in 1978, Hidalgo County

received a check in the amount of $7,873

for back taxes for Rio Rico.

May 2016 ...

Crisis On The Border ... Over A Century Ago

Crisis is defined as a time of intense difficulty, trouble, or danger.

While the Valley has certainly faced a challenge during the past few

years regarding the increasing numbers of Central American refugees, it

can hardly be considered a crisis as referred to by mainstream media

throughout the country. If you want to understand what a true crisis on

the border is, you only need to go back in time one hundred years.

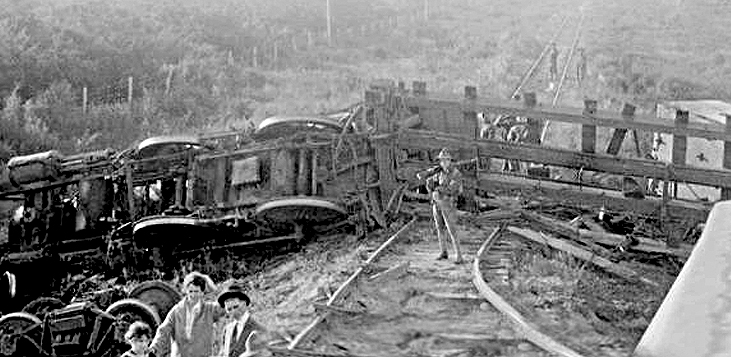

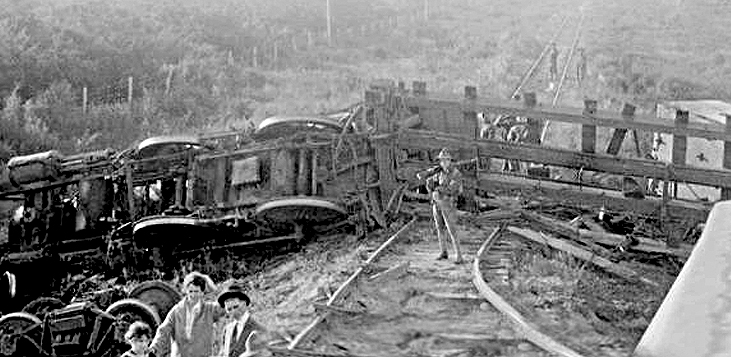

On the night of October 18, 1915, around 10:45 pm, the St. Louis,

Brownsville & Mexico Railroad train suddenly derailed about seven

miles north of Brownsville.

A group of sixty men swarmed the passenger cars shooting Anglos on

sight. In a span of only about fifteen minutes the train's engineer and

three passengers were killed and the fireman and three other passengers

were wounded. The raiders made off with about $325 in cash in addition

to jewels, watches and even shoes. They then headed across the Rio

Grande returning to Mexico.

History books declare that the holdup was the work of Tejanos and

Mexican renegades, using the chaos of the Mexican Revolution for their

own purposes; to get money, to kill whites or maybe even to wrest

control of the Southwest from America. But this was more than just an

extreme case of banditry. The wreck and robbery was part of a Mexican

invasion of Texas as laid out in the Plan de San Diego resulting in the

Bandit War.

The Plan de San Diego called for a popular uprising of American Blacks,

Hispanics and Indians in February 1915. They would capture Texas, New

Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and California which would all revert to

Mexican control. Most alarming to American residents living near the

border was the fact that the Plan ordered all Anglo males over the age

of 16 to be killed.

It is widely believed that the man behind this sinister plot was none

other than Venustiano Carranza, the brilliant, devious and ruthless de

facto ruler of Mexico at the time. It is unlikely that he really

believed that Mexico could regain control of Texas and the Southwest.

But the Plan could get him diplomatic recognition from the US

government. The key, of course, was to keep Carranza's role hidden from

the Americans and to blame his rivals or his Tejano allies for the

violence that was to come. He played on the arrogance of U.S. and Texas

officials, who believed that no Mexican was smart enough to pull off

such a deal.

In spite of the February start date, the offensive didn't really begin

until July 1915. A band of 30 Mexican raiders roamed across south Texas,

robbing and threatening residents, and killing at least one Anglo.

Under pressure from residents and commercial interests in the region

Texas Gov. James Ferguson created Texas Ranger Company D and appointed

Henry Lee Ransom as its first captain. Ransom was ordered to clean

things up using all means necessary. With a "shoot first and ask

questions later" reputation he was more than happy to comply.

On August 3, 1915 U.S. forces and a group of raiders battled at Aniceto

Pizaña's ranch, about 18 miles north of Brownsville. Pizaña, along with

former Cameron County Deputy Sheriff Luis de la Rosa, would become known

as combat leaders of the Plan de San Diego.

In the town of Sebastian, on August 6, a store was robbed by bandits who

captured and murdered two Anglos. Rangers and local law officers

responded by attacking the ranch of a suspected Plan member, killing him

and one of his sons.

Responding to reports that a Plan raid was in the works, a detachment

from the Army's 12th Cavalry, along with some customs inspectors and the

local deputy sheriff, went to Norias, home to the sub-headquarters of

the legendary King Ranch. On the evening of August 8 about 60 riders

attacked.

The American defenders held out for more than two hours, even though

four of them were wounded. The bandit leader was shot and killed during

the fighting and his followers decided to retreat, leaving seven Mexican

corpses behind.

Tensions were running high. The Anglos were in fear of a local uprising,

while Tejanos feared brutality from the Rangers. Governor Ferguson

responded to the crisis on the border by increasing the size of the

Ranger force and ordering almost all of it to south Texas.

General Frederick Funston, the commander of the Army's Southern

Department, believed that more raids were imminent. He positioned 40

small Army detachments, a total of 2,500 men, throughout South Texas.

Brutality was present on both sides of the conflict. Some Tejanos and

Mexicans who were thought to be tied to the Plan were simply killed, no

trial necessary. The Mexicans attempted a number of assassinations of

U.S. officials; a couple of which were successful. On September 24,

nearly 100 Plan fighters, accompanied by Carranza soldiers, crossed the

Rio Grande and attacked the town of Progreso. They looted and burned the

place, and captured Army Pvt. Richard Johnson, taking him with them

when they retreated back to Mexico. Johnson was executed, and two

Carranza men removed his ears as souvenirs. His head was cut off and

placed on a pole for the Americans to see.

On October 19, 1915 the United States gave diplomatic recognition to

Carranza as president of Mexico. Five days later, he ended the Bandit

War. True to his ruthless nature, Carranza abandoned his Tejano allies

leaving them to be captured or killed.

It is not clear just how many people died during the four months of the Bandit War. Some estimates go as high as 5,000.

What is clear is that this was truly a time of crisis along the border and the challenges we face here today pale in comparison.

August 2016 ...

Pancho Villa's Forces Fire Upon American Pilots Near Brownsville

In September 1914 the 1st Aero Squadron

was organized based at North Island,

San Diego, California. In response to

tensions along the Texas - Mexico border

four pilots and three planes, Curtiss

JN-2s, were transferred to Ft. Brown in

Brownsville, Texas in March 1915.

On April 20, 1915 Byron Q. Jones took

off from Fort Brown with aviation pioneer,

Lt. Thomas D. Milling. Their mission

was to scout the forces of Pancho

Villa who were staging in the Mexican

city of Matamoros.

About 15 minutes into the flight, the

U.S. aircraft drew the attention of Villa's

forces, who opened fire with at least

one machine gun, as well as small arms.

Jones was able to maintain his composure

under fire. He opened the throttle

and nosed up, climbing to 2,600 feet to

avoid the gunfire. He maneuvered away

from the river and was able to return

safely to Fort Brown.

This marked the first time ever that an

American pilot was fired upon during an

aerial combat mission.

An important mineral for

human nutrition, salt was also a critical

ingredient for preserving meat and

animal hides. Early inhabitants of South

Texas obtained salt for their own uses,

and possibly for trade as well.

An important mineral for

human nutrition, salt was also a critical

ingredient for preserving meat and

animal hides. Early inhabitants of South

Texas obtained salt for their own uses,

and possibly for trade as well.

Introduced commercially in the

region in 1904, citrus fruit culture has survived severe freezes in

1949, 1951, 1961, 1983 and 1989.

Introduced commercially in the

region in 1904, citrus fruit culture has survived severe freezes in

1949, 1951, 1961, 1983 and 1989.

A group of sixty men swarmed the passenger cars shooting Anglos on

sight. In a span of only about fifteen minutes the train's engineer and

three passengers were killed and the fireman and three other passengers

were wounded. The raiders made off with about $325 in cash in addition

to jewels, watches and even shoes. They then headed across the Rio

Grande returning to Mexico.

A group of sixty men swarmed the passenger cars shooting Anglos on

sight. In a span of only about fifteen minutes the train's engineer and

three passengers were killed and the fireman and three other passengers

were wounded. The raiders made off with about $325 in cash in addition

to jewels, watches and even shoes. They then headed across the Rio

Grande returning to Mexico.